Stimulating Smart People to Learn

Often, we blame others for lack of change, but where does the blame really lie?

I was just reading Chris Argyris’s classic HBR article Teaching Smart People How To Learn. In it he describes a situation he consulted on with a management consultancy. The people involved were recruited because they are highly educated and had MBAs from the top three or four US Business schools. Clearly these people were smart, but Argyris contends that although they were extremely good at single-loop learning, being able to solve problems presented to them, they were not so good at double-loop learning, being able to analyse their own performance to be better next time. He used the example of consultants’ managers trying to get them to analyse their own performance after a difficult consultancy intervention. The consultants consistently blamed others including the managers, and even the clients, frequently “bad mouthing” them behind their backs, and took no responsibility for their own part in the situation. Argyris described the discussions as “defensive”.

I have witnessed this myself with management consultants, being a Continuous Improvement (CI) professional I am often in the unique position of being an employee of a company that hires in management consultants, who then talk with me for a “different” insight. During these discussions I have heard consultants blaming the senior management for their (the consultants) inability to stimulate the required behaviour change. I came to work at a site that had had two consultants embedded for some months. I shared an office with them and of course would discuss the situation with them, they blamed the lack of cultural change on the site management. Later in the discussion they blamed the site leader’s behaviour on the regional leadership, “these leaders have all managed this site at one time or another and so have a vested interest in proving that there is no other way to run the site so it doesn’t look like they weren’t good leaders of change when they managed the site”.

I am not sure about this reasoning, perhaps it is true, but perhaps the regional leaders had been promoted beyond mere site leadership and were wholly focused on looking good in their current position for advancement to corporate leadership.

This brings us back to the consultants and double-loop learning. Clearly these consultants were displaying the same characteristics as Argyris’s consultants, and by extension, do I as a CI professional do the same thing? I have joined in with discussions with my colleagues on the expansion of CI culture in our organisation. We had the experience of the lower levels really getting on board with the work we were doing but it was really hard to grow it out beyond these oases of improvement culture. Commonly we attributed this to the leadership of the target organisations, “if only they would see how well this works and get on board”. In these conversations we were displaying the same behaviours as the managers we were targeting, they were good at dealing with the problems they faced every day, firefighting, but were not so good at stepping back to look for a better way.

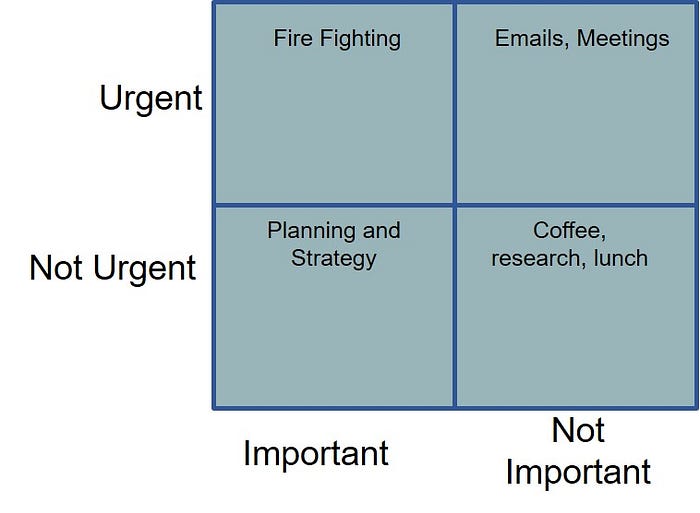

I had a conversation with a friend who was a Managing Director, and he saw this double-loop learning wasn’t happening with his leadership team. We discussed causes and how to break this behavioural deadlock. He was aware that his rhetoric, although important, couldn’t cause lasting change on its own. We decided to take the team away from their normal daily work for five days to think about how to think differently, we provided them with a problem that on the surface looked like single-loop learning but was really double-loop learning. The problem we posed was how do we change this organisation to no longer rely on fire fighting. Getting them to comprehend this problem was a problem in itself. This required the MD’s leadership; the MD drew-up a 2-by-2 matrix labelling the axes important/ not important vs urgent /not urgent.

We got the team to provide examples of tasks they did that would fit into each quadrant. Important & urgent: Safety responses, customer queries, problem-solving, firefighting, Urgent & not important: emails, meetings, Not-important & Not urgent: Lunch, coffee and personal stuff e.g. researching holidays (the MD said that as long as the work got done he was ok with people doing that sort of thing), Not-urgent & Important: Building strategy.

The team then told us the amount of time they spent doing these quadrants, 70% on firefighting, 25% on emails and meetings, 5% on coffee, lunch and “research” and 0% on planning and strategy.

Very telling, but perhaps this situation was because they didn’t know any better, so we asked them what proportion of time they “should” spend on each quadrant? 30% on firefighting, 15% on emails and meetings, 15% on coffee, lunch and “research” and 40% on planning and strategy.

This largely lines up with Stephen Covey’s original model, so they knew what they should be doing. So, what was stopping them? They said the time to do it, they knew they needed to carve out time for strategy and planning, “but the urgent stuff gets in the way”. Clearly time would help but leadership direction was important too, to make their team step-back and do the double-loop learning. The rest of the week the Leadership team stood back and created a new way to run the business, to get as close to silent running (i.e. zero firefighting) as possible. They planned how to pipe real-time relevant data into their weekly meeting in a form the whole team would understand, they planned layered visual management meetings so everyone (the whole staff not just managers) would have all the information they needed when they needed it to make good decisions as quickly as possible at the lowest level possible. Later they each enforced their people to use these meetings; to do the double-loop learning that was so urgently required. This set-up ran for a year until the corporate leadership carried out a reorganisation.

Chris Argyris in his article said to get the consultants out of their single-loop learning rut, the management led the way by displaying real double-loop learning with their teams and changed the way they behaved: real openness in passing on information and opinion, and not saying things like “think of the organization as a whole” and following-up with asking for specific actions by department, e.g. departmental budget cuts.

In effect, the case study exercise legitimizes talking about issues that people have never been able to address before. Such a discussion can be emotional — even painful. But for managers with the courage to persist, the payoff is great: management teams and entire organizations work more openly and more effectively and have greater options for behaving flexibly and adapting to particular situations.

Chris Argyris (1991)

In my CI Team we set a time aside both daily and weekly to teach each other and to discuss issues we were facing, it took a while and some good management from my boss to really allow us to open-up and admit “we partly create the problems we face and we have responsibility for this”, Gregory Bateson (1979).

Darren Clyde has spent 15 years working with organisations and teams to reduce cost and effort of doing business. He has worked with many leadership teams around the world on developing a continuous improvement and learning culture in their organisations.

References:

Argyris, C (1991), Teaching Smart People How to Learn, Harvard Business Review, Volume 4, Number 2, Reflections

Covey, S (2004), 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, Simon and Schuster

Bateson, G. (1979), Mind and Nature, Bantam, Toronto